This research report presents the findings of a sociological study conducted as part of Work Package 2 of the “STREAM IT” project. The study’s primary objective was to provide a foundation for the project’s programs and initiatives aimed at encouraging girls and young women to pursue education in chosen STEAM fields. Designed to offer a current and comprehensive view, the research examines women’s status in STEAM domains across Europe, pinpointing key points in girls’ educational paths where targeted interventions could be impactful.

The research methodology was organised around three primary tasks. Task 2.1 involved a thorough review of existing sociological literature to highlight key findings and concepts that could inform the project’s approach. Task 2.2 focused on exploring female students’ experiences and perspectives, while Task 2.3 involved interviews with experts from formal (secondary and tertiary) and non-formal educational institutions to gather insights into current practices and perspectives in STEAM education. The analysis also aimed to assess institutional awareness of gender barriers and the support provided to girls/young women/women in ECR in the STEAM fields.

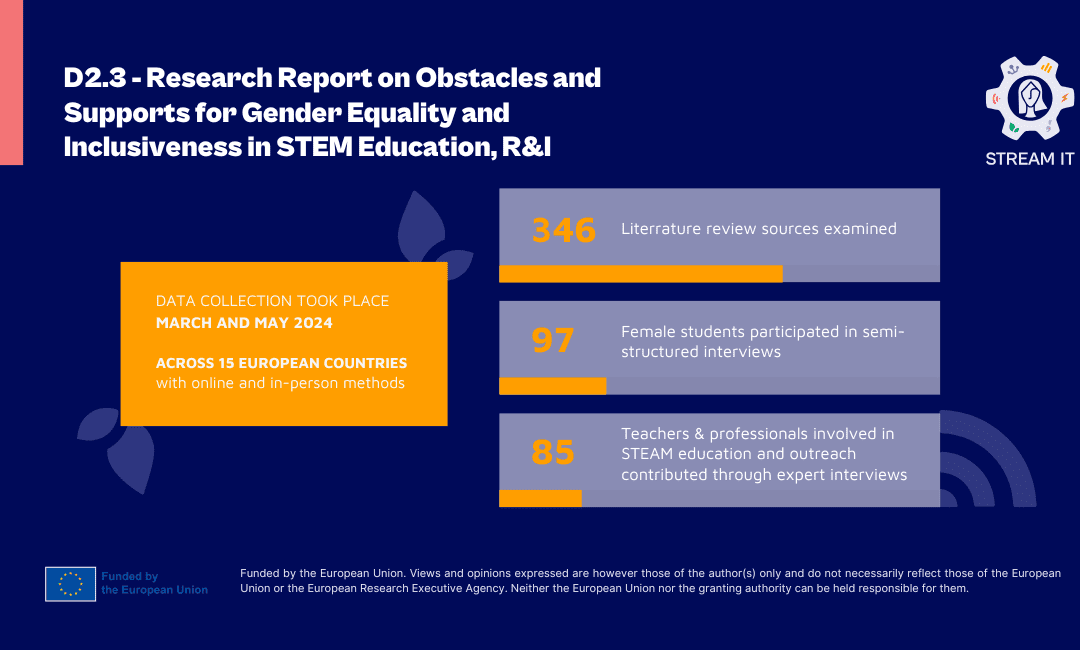

The data collection took place between March and May 2024 across 15 European countries, with online and in-person methods. Anonymity was provided to all participants who consented by signing an informed consent form. In total, the literature review examined 346 sources, while 97 female students participated in semi-structured interviews, and 85 teachers and professionals involved in STEAM education and outreach contributed through expert interviews.

LITERATURE REVIEW

A diverse array of methodologies is employed in studying girls and women in STEM education and professions, although quantitative approaches get the lion’s share of scholarly attention, qualitative and mixed-methods research are also present and complement the former quite well. In terms of geographical coverage of populations studied, a wide majority of publications cover Western perspectives (mostly U.S.), but one can also identify studies focusing on the Global South or Eastern Europe, which enables a more nuanced understanding and shows efforts to decolonize scholarship. Most research covers the experiences and situations of students enrolled in undergraduate studies, and the educational experiences from early childhood to pre-university are documented to a lesser extent: overall, studies reveal that there is no specific time when we start losing girls from a STEM track, that this leak happens throughout the pipeline – due to individual, institutional, and cultural factors -, substantiating the idea that efforts to close the gender gaps need to be made throughout their education.s a foundation and starting point for this collective set of methods and tools, as well as clarify the research objectives pursued by the four tasks.

INTERVIEWS WITH FEMALE STUDENTS

The semi-structured interviews conducted with students across all three-degree levels provided a nuanced view of the social realities young women face in STEAM fields. This report focuses on their motivations, as well as the challenges and opportunities they encounter. One of the main motivations for choosing studies in science, mathematics, or technology is personal interest and aptitude, although influences from family and school also play a significant role. Additionally, STEAM programs’ strong social reputation and promising career opportunities make these fields attractive to young women. Among the key challenges these students face, gender stereotypes and expectations were noted as primary obstacles. These stereotypes reinforce the notion of a disconnect between women’s traditional social roles and the ideal image of a STEAM professional. Common forms of exclusion and discrimination stem from culturally ingrained concepts of “masculine” and “feminine” traits. Furthermore, a lack of supportive social relationships and an often unwelcoming, predominantly male environment in classrooms and faculties contribute to a diminished sense of belonging among female students. Finally, concerns about balancing work and family expectations frequently lead women to question their place in STEAM fields.

Despite these challenges, we identified three main sources of satisfaction for female students. A welcoming, inclusive environment with supportive social and professional relationships provide strong motivation to persist in their studies. Surprisingly, social norms that alleviate pressure on women to achieve high financial success allow many to choose careers aligned with their passions rather than financial needs. Lastly, the perception that gender inequalities are gradually diminishing, following a “natural” path of positive progress, reinforces women’s sense of legitimacy in pursuing STEAM education and careers.

EXPERT INTERVIEWS

The first subchapter explores perspectives from higher and secondary education representatives regarding increasing women’s participation in STEM. It was revealed that opinions vary on whether targeted interventions, especially in fields with already high female representation, are needed. Perspectives on the means of achieving gender balance is also diverse: only a few respondents advocate structural changes, many see women’s inclusion as vital for diverse leadership and innovation, although essentialist views on the gendered contributions to team dynamics could be detected.

The second subchapter explores the institutional view and understanding on the obstacles girls and young women encounter in STEM education from primary school through professional career stages. Key findings reveal that, despite progress in gender equality in the fields of STEAM, many barriers persist including that societal stereotypes and family expectations discouraging girls’ STEM career aspirations, educators may unconsciously reinforce biases at primary and secondary level, there are insufficient institutional support at tertiary level and university students often experience subtle exclusionary behaviours from peers and faculty. Societal expectations and institutional policies often lack adequate family support systems, creating barriers in hiring, advancement, and re-entry post-maternity for women researchers.

The third subchapter examines the strategies and approaches educational institutions employ and advise to support girls and young women in STEM fields. It reveals that while some institutions recognize the need for dedicated support (e.g., policy reforms, inclusive learning environment), there is limited formal commitment to institutional reforms, especially at the tertiary level. The interviewees highlighted the importance of individual empowerment through self-confidence building, mentorship, role models. Challenges in supporting girls and women in STEM education includes the limited formal support at senior management levels within universities and the reliance on volunteer-driven initiatives rather than systematic programs. Despite differing views on the necessity of gender-specific support, there is consensus on the role of supportive school environments and innovative methodologies that align with girls’ interests to bridge the gender gap in STEM.

The fourth subchapter presents a series of expert recommendations aimed at increasing girls’ participation in STEM fields. The following main recommendations for the area in need of intervention emerged:

1) Experts emphasised the value of early development of critical skills, such as problem-solving, research abilities, and leadership, as essential for building a solid STEM foundation and bolstering girls’ confidence and interest. 2) The findings indicate that gender-sensitive training for educators is necessary to prevent the unintentional reinforcement of gender stereotypes that may deter girls from pursuing STEM careers. 3) Innovative, experiential learning approaches that prioritise real-world applications and creativity were frequently recommended. 4) Role models provide girls with relatable examples of success in STEM, helping them visualise their potential paths in these fields. 5) The application of gender sensitive methodologies in early education is a necessity. 6) Financial barriers remain a limiting factor for many girls, particularly those from underprivileged backgrounds. 7) Community programs and parental support are seen as vital in breaking down societal barriers and sustaining interest in STEM.