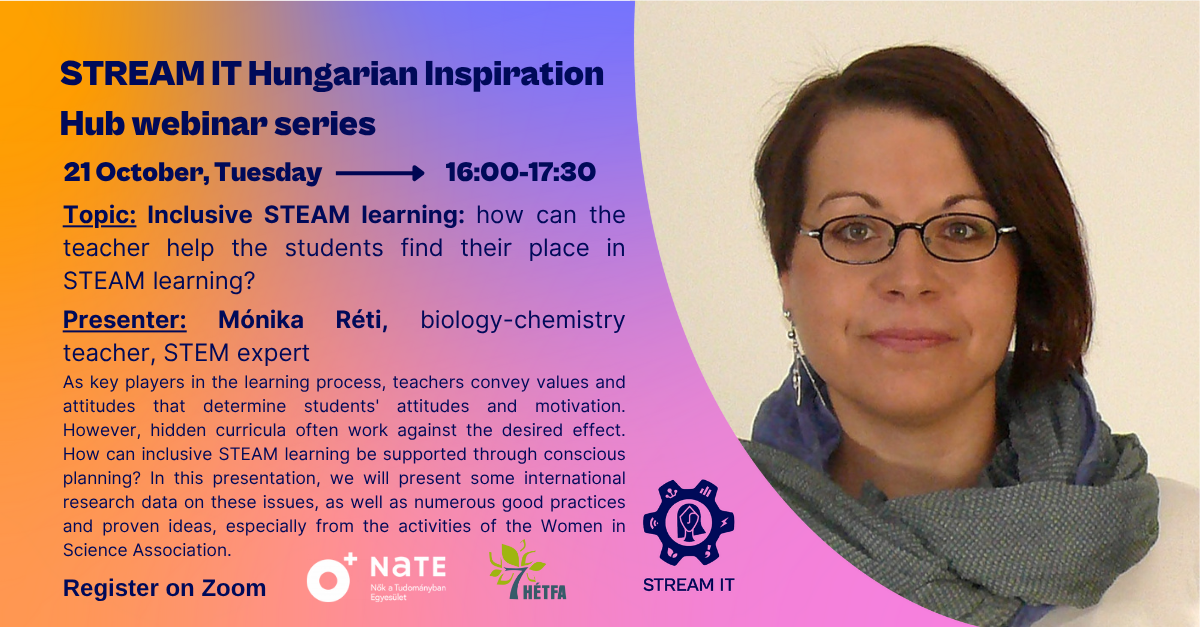

Teachers occupy a central position within the learning process, serving as mediators between curriculum, knowledge, and learners’ individual experiences. In STEAM education, their influence is particularly important, as they shape the learning environment, maintain motivation, and foster an inclusive atmosphere that can determine students’ academic success and future career orientations. The Hungarian Inspiration Hub’s third webinar addressed precisely this question: how can teachers actively contribute to constructing learning environments that ensure equal opportunities, stimulate engagement, and strengthen confidence among all students, with special attention to the participation of girls in STE(A)M-related learning processes. Our invited speaker was Mónika Réti, a high school biology and chemistry teacher who has participated in the implementation of more than 30 international STEM projects since 2008 as an expert, external and internal evaluator, policy advisor, researcher and analyst. In this article, we summarise the main points discussed during the webinar featuring Mónika Réti.

The Significance of Teachers in Building Inclusive Learning Environments

Inclusive education extends far beyond the application of differentiated teaching methods. It is rooted in teachers’ attitudes, beliefs, and perceptions of learners’ abilities and potential. Even when teachers consciously strive for fairness and equality, implicit biases often influence their classroom interactions and pedagogical decisions. Empirical research has repeatedly demonstrated that, in STEM classrooms, boys tend to receive more teacher attention, are called upon more frequently, and are engaged in interactions with teachers that are both physically (e.g., eye contact) and cognitively more significant. Teachers often respond to boys’ contributions with factual or analytical comments, while girls’ performance is more commonly praised in terms of diligence, neatness, or persistence. Such subtle, yet persistent patterns of differential feedback may have long-term effects on students’ self-perception and motivation.

These gendered dynamics can lead girls to underestimate their intellectual capacities, experience heightened anxiety toward subjects such as mathematics or physics, and gradually disengage from fields where they perceive lower levels of belonging or self-efficacy. Therefore, a central element of inclusive pedagogy is teachers’ continuous self-reflection, aimed at recognising and mitigating unconscious biases. Inclusive teaching does not mean identical treatment of all learners; rather, it requires the ability to respond consciously to students’ diverse backgrounds, learning needs, and cognitive as well as emotional conditions. Teachers must view diversity not as a difficulty to be managed but as a resource for mutual learning and growth.

Gendered Classroom Dynamics and Their Implications

Classroom observations reveal that gender imbalances are often perpetuated by habitual interaction patterns. Boys are more frequently chosen to answer questions, approached more often during classroom monitoring, and provided with feedback that emphasises reasoning, problem-solving, and creativity. Girls, in contrast, are more often acknowledged for their accuracy and compliance, while their innovative or analytical contributions may remain unnoticed or undervalued. Over time, this reinforces a learning culture in which boys are positioned as active knowledge producers, whereas girls become associated with passive correctness and reliability.

As a consequence, many girls hesitate to take intellectual risks, refrain from volunteering answers unless they are certain of correctness, and engage less confidently in experimental or exploratory learning situations. This dynamic contributes to the internalisation of gendered expectations regarding who is “naturally talented” in science and technology. Consequently, inclusive pedagogy must explicitly address these interactional asymmetries through conscious reflection and deliberate classroom structuring.

Institutional and Cultural Preconditions of Inclusion

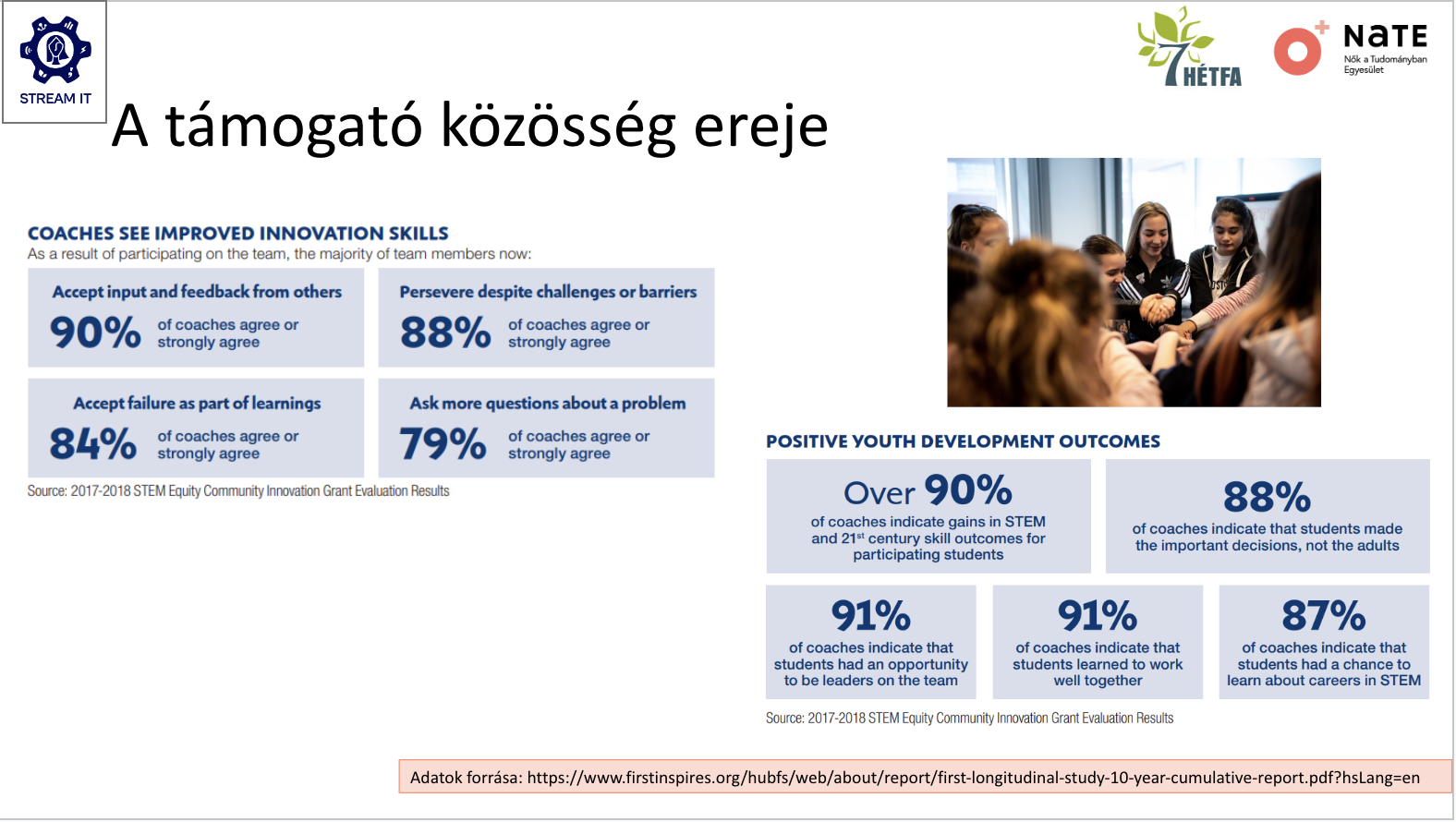

Although teachers play an indispensable role in shaping the classroom climate, the creation of inclusive learning environments cannot rely solely on their individual commitment. The creation of inclusive learning environments requires systemic support and an institutional culture that consistently promotes equality, diversity, and collaboration. Supportive leadership for inclusive values, ongoing teacher development, and structures that encourage reflective practice are crucial for lasting success. Inclusion is therefore not an act of individual goodwill but a collective pedagogical and organisational responsibility, embedded within a school’s ethos and supported by broader educational policies.

Pedagogical Strategies and Practices Promoting Inclusion

Several pedagogical strategies can enhance inclusivity in STE(A)M education when consciously and consistently applied. The quality of feedback represents one of the most powerful levers for change. Teachers’ feedback should focus on students’ concrete achievements, reasoning processes, and problem-solving strategies rather than on general personal traits. By valuing intellectual effort and creativity instead of abstract notions of “smartness” or “diligence,” teachers communicate that ability is malleable and that progress results from engagement and reflection.

The deliberate organisation of group work is equally important. In mixed-gender groups, boys tend to assume leadership positions, while girls frequently take supportive or passive roles. Teachers can counteract this by assigning specific, intellectually demanding tasks to all participants and by explicitly rotating leadership roles. In some contexts, particularly at early learning stages, single-gender groups may help girls strengthen their self-confidence and agency before transitioning into mixed collaborative settings. Such practices should, however, always aim at long-term integration and equality rather than segregation.

Active and authentic learning methods, such as inquiry-based learning, project-based approaches, and experimentation, also play a crucial role in promoting inclusion. These methods not only foster critical thinking and collaboration but also allow students to connect scientific knowledge with their everyday experiences and personal interests. When learning becomes personally meaningful, students from diverse backgrounds can recognise themselves within the subject matter and feel ownership of their learning process.

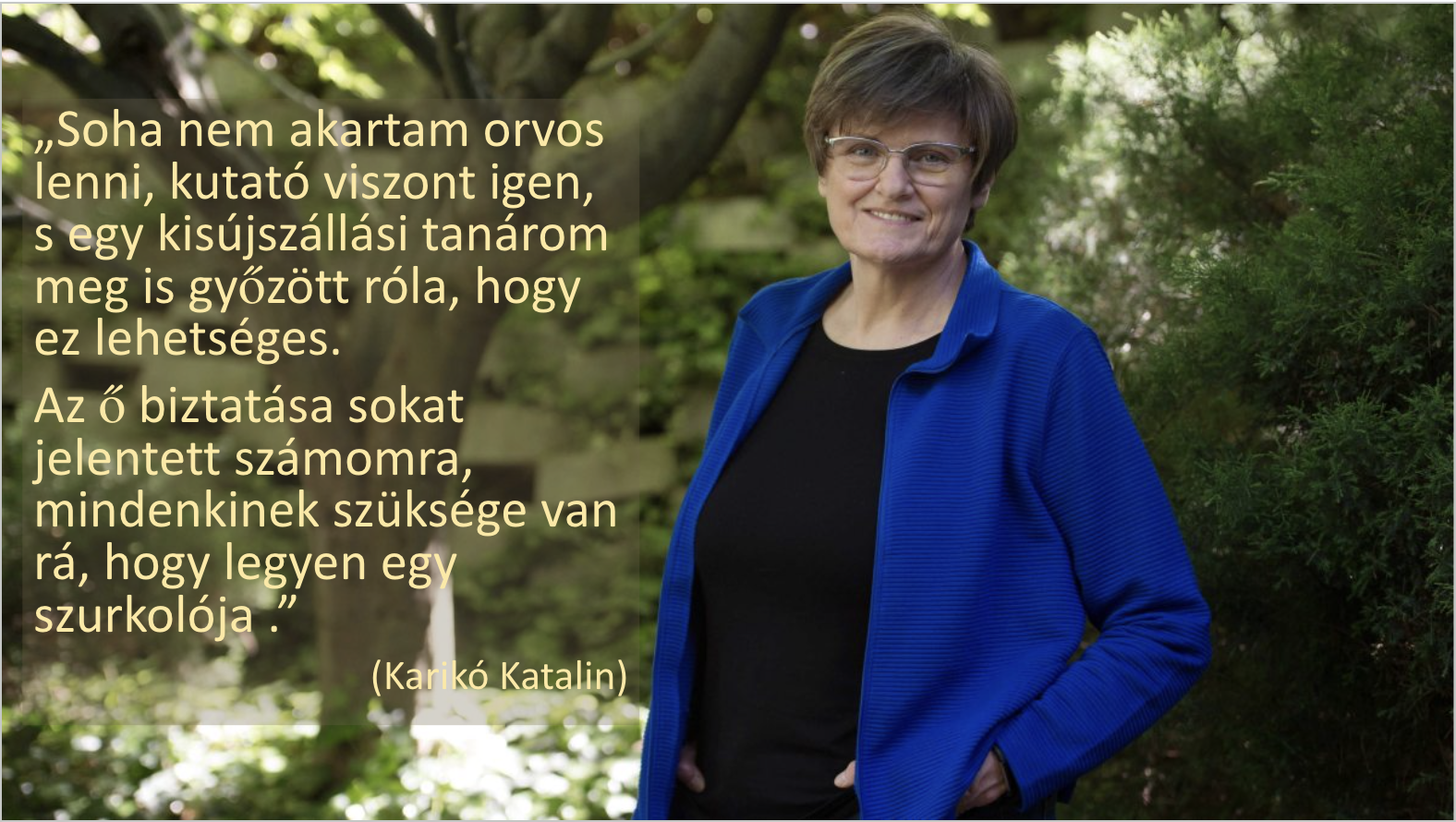

Furthermore, the visibility of diverse role models is of paramount importance. Introducing female scientists, engineers, and innovators in teaching materials and classroom discussions helps dismantle the persistent stereotype that associates scientific excellence with masculinity. Schools and teachers can collaborate with research institutions, universities, or industry partners to expose students to a wide spectrum of professional trajectories, thereby broadening their imagination about possible futures.

Finally, the integration of the arts into STEAM education has a distinctive role in fostering inclusivity. The arts engage emotional, creative, and reflective dimensions of learning, activating brain regions associated with long-term memory and empathy. By connecting rational inquiry with imaginative expression, the arts help students, especially those who may not initially identify with traditional science learning, to access content through alternative cognitive and affective pathways. In this sense, the “A” in STEAM serves as both an equaliser and a catalyst for deeper engagement, transforming scientific learning into a holistic learning experience.

If you would like to listen to the whole webinar on inclusive learning environments in STEM, you can access the recording via this link.

Author

HÉTFA Research Institute

Katalin Oborni, Senior Project Manager at HÉTFA’s Division of International Cooperation, coordinating the STREAM IT and RE-FEM projects, holds a PhD in Sociology and master’s degrees in History, Pedagogy, and Gender Studies. Her research covers work dynamics, gender equality, women’s entrepreneurship, and leadership. With extensive experience coordinating Erasmus+ projects and managing Horizon and CER EQUAL initiatives, Katalin’s research and coordination expertise ensure effective project management and delivery. She is also the Gender officer for a COST Action project (PROFEEDBACK) coordinated by HETFA RI.